Not Leaving the Monastery

“What I saw or heard or felt came not but from myself—and there I found myself more truly and more strange.” —Wallace Stevens

Zuisei Goddard speaks from the heart about her own spiritual journey and her ongoing commitment to practice as she steps further into lay life.

This talk was given by Zuisei Goddard. For the transcript, scroll down.

This transcript is based on Zuisei’s notes and might differ slightly from the final talk.

At Blackwater Pond

by Mary Oliver

At Blackwater Pond the tossed waters have settled

after a night of rain.

I dip my cupped hands. I drink

a long time. It tastes

like stone, leaves, fire. It falls cold

into my body, waking the bones. I hear them

deep inside me, whispering

oh what is that beautiful thing

that just happened?

A student offered me this poem in response to the letter I sent out last week. As most of you know, I wrote to the sangha saying that given the end of my marriage, I have been reflecting on a number of things. One of them is how to best continue my spiritual path, and the particular way in which I have chosen to live my life in the dharma.

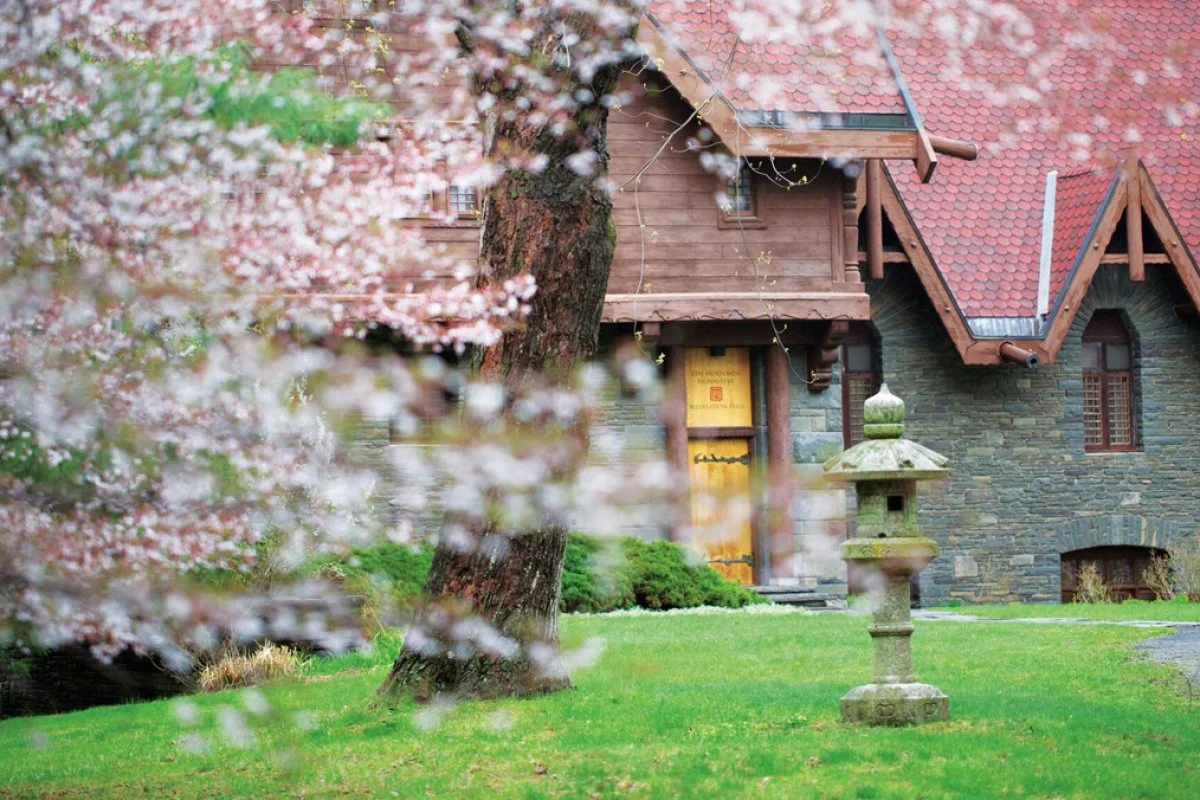

After much reflection and a number of conversations with my teacher, I decided to take some time off from teaching and to step out of the Monastery and the schedule. This is so I can have the time and space to be with myself. So I can listen to my bones whispering, having been woken up in no uncertain terms. So I can explore what it would be like to continue practicing and teaching the dharma, but this time from within a true lay life.

I came here in my early twenties, straight out of college as a response to an urgent question.

For years I’d been looking at the world and I’d been looking inside me, and so much of what I saw I did not understand. I did not understand why it seemed to be so hard to live a human life.

Why, amidst so much abundance—which I and the people around me certainly had—why amidst so much beauty and wonder, there was also so much sadness and strife.

I didn’t understand why, when what we were all searching for was happiness, we could hurt ourselves and one another so insistently, so… inevitably. But then I began to wonder, is it really inevitable? Is there perhaps another way to live? And by a series of what I can only call blessings, I found my way to the Monastery.

So a few years later, after having lived here and tried on the life, I left home in earnest to become ordained as a monk. I left home in order to come home. And I did this while in a loving, intimate relationship—which was not easy. Navigating my monastic vows and my marriage vows was not easy. I did not do it well in many ways. Still, it was the reason I took off my monk’s robes four years ago—in order to have a bit more balance. So I was neither a monk nor quite a lay practitioner. I travelled, for a few years, a third path, and it was good.

Now I am leaving home again in order to come back home to myself. The home I was never apart from, though I didn’t know this. For years I didn’t know you’re never actually far from home. Just as you never take a step without the ground rising to meet you. It never fails to meet you. I know it doesn’t always feel that way. Sometimes it feels like you’ve fallen flat on your face, but I’ve come to see that that’s still the ground meeting you. Like in that koan—you use the ground to get up from the ground. There’s no other way to do it.

Although these last few months have been very full and very difficult, they’ve also been very affirming of my life in practice. Someone asked me if I wanted to continue practicing. Do I still want to sit? YES is the answer, a resounding YES. I’ve said many times before and I say it even more now, zazen is for me a lifeline. It is a refuge. It is me lashed to the mast of my little boat as ten-foot waves pound the hull. Or as a gentle breeze stirs the tiniest of whitecaps. Or when there is no wind and the water is deep and still and clear as glass. There I am, on my little raft, with everything that I need, really. Although other gifts keep floating my way: places to stay, cars, dinners, cookies…gifts that I couldn’t possibly repay if I worked as hard as I could for the rest of my life.

This boat is a bit like Vimalakirti’s house. It’s small when you look at it from the outside.

But, there are legions of bodhisattvas riding in it. They all fit perfectly inside this tiny space and they don’t even jostle one another. They come with tools and books and songs and poems, offering medicine. Offering solace or company or a pair of ears or a pair of arms. And because of them, and because of the nature of the ocean I’m on, inevitably the tossed waters settle.

One thing I’ve learned having been adrift at sea enough times, is that if you give them time, and trust and non-interference, the waves inevitably settle. Even when they don’t settle, there’s a place in which they’re still. Think of being on a plane high over the ocean and you look down and it looks calm, like glass. It’s when you get closer, when you get right in it, that you see the individual waves with their frothy heads.

Part of the work is to not get lost in the minutiae of each wave. To keep the mind large and expansive, where it does have a chance to settle. No, where it is naturally still. And when your view is large you also remember that all of those individual waves are ultimately one ocean. I confess I love that moment when you leave dry land behind. It’s a moment of awe in every sense of the word: wonder, fear, reverential respect—all of which I’ve been feeling lately, mixed in with a few more things.

But, there is that moment, where there is only sea and sky and air all around when, without markers, and every possibility exists in its entirety. Where, depending on what you choose, a potentiality becomes an actuality—as they say in quantum physics—and this leads to other potentialities, that lead to certain actualities, and so on… All of that open space, and you can go in any direction. Well, perhaps not any direction, as there is karma and history and circumstances. But, in many more directions than when you’re landlocked. Though I suppose that part of the risk of going out to sea is you have to be willing to be lost for a little while—or a long while, I don’t know.

There’s that story of two fishermen who get lucky one day and catch a full net of carp.

Thinking they can go back to the same spot the next day, and repeat their good fortune, one of them takes a piece of charcoal and draws a big X on the side of boat. I see myself wanting to do the same when I get nervous about stepping into the unknown wanting to paint a big, fat X on the side of my boat, on my robe, that says, “Z was here,”—no, that says “Z is here” and she will still be here.

The great master Zhaozhou, said, “If you sit steadfastly without leaving the monastery for a lifetime, and do not speak for five or ten years, no one will call you speechless. After that, even buddhas will not equal you. What kind of invisible path is there between the lifetime and the monastery? Just investigate steadfast sitting…Steadfast sitting is one lifetime, two lifetimes, not merely one time, two times. If you sit steadfastly without speaking for five or ten years, even buddhas will not ignore you. Indeed, such steadfast sitting without speaking is something buddha eyes cannot see, buddha power cannot pull away, and buddhas cannot question. Even if you sit steadfastly, silently, without leaving the monastery for five or ten years, Zhaozhou says, no one can call you speechless because silent, steadfast sitting is still expression. What kind of expression is it?”

Thomas Merton once said: “What counts is not to count and not to be counted.” (A little ironic coming from one of the most famous monks of recent times).

What kind of invisible path is there between the lifetime and the monastery? Dogen asks.

That’s what I would like to find out. What kind of invisible path is there between the lifetime and the monastery, between past, present, and future. Between the monastery and the world?

How do you leave the monastery without leaving it? Without it leaving you? Really, practically, not in an abstract Zen talk kind of way.

Daido Roshi used to say, “Entering the world without having left the mountain.” This is the challenge of lay practice. Actually, it’s the challenge of practice, period. Because every time we step off our cushion we’re leaving the mountain and entering the world. Every time we abide in stillness or engage a thought. So how do you bring the mountain with you? How do you not forget where you came from—quite literally where each of us comes from? How do we not make mountain and world two?

Dogen also says: Walking, sitting, and lying down without leaving the monastery is the practice of no one will call you speechless. Although how the lifetime comes about is beyond our knowledge, if you activate without leaving the monastery, you do not leave the monastery.

How the lifetime comes about is beyond our knowledge. How true that is. Every time I’ve thought I’ve known my lifetime, known my tomorrow, I’ve been shown that no, I don’t actually know. As Shugen R. so often says, we assume that tomorrow will be the same as yesterday.

But, there really is no evidence to support that belief, other than our own desire that it be so.

This is not an unreasonable wish, we do crave and work for continuity, for consistency. But within that continuity, how do we make room for change? Well, whether we make room for it or not, change happens, because that is the nature of things, of life—to change, to become, to constantly unfold.

I am reading a book about quantum gravity, Reality Is Not What It Seems. And in it, Carlo Rovelli quotes the philosopher Nelson Goodman who said: “An object is a monotonous process.” Meaning, an object is not really a thing but an event. It’s a process slowed down for a bit so that for a short while it appears to be unchanging (like a wave that appears to be its own thing, yet is part of that vast ocean). We too are processes, says Rovelli, “for a brief time monotonous.” Though maybe “consistent” would be a better word, since monotonous makes it sound like we’re boring. I think life is many things, but it’s not boring. Boredom is a lack of attention. Boredom is letting yourself be swept up by the world and forgetting about the monastery. Boredom is thinking you see, thinking you know.

At Blackwater Pond the tossed waters have settled

after a night of rain.

I dip my cupped hands. I drink

a long time. It tastes

like stone, leaves, fire.

It’s easy to think when the water gets choppy there is something wrong. Easy to wonder, what if I had a bigger boat, or a different one? What if I had a boat that didn’t leak, didn’t list to one side, but always went straight ahead and infallibly? What if early on I’d taken a different route, what if I’d started earlier or later, what if I’d brought more people along? Disruption, by definition, is uncomfortable. And although it is woven into the very fabric of things, to change,

It’s not so easy to accept it. It’s not so easy to let that freezing cold water burn. To let it sit in your gut heavy, like a stone. To let it flutter in your belly like leaves in autumn, and not rush to fix it. By that I mean both fix in place and mend it.

I don’t find it easy. It requires great trust and infinite patience. Like sitting shikantaza. There’s nothing to do, nothing to fix, nothing to make better. And for a while, when I first started doing shikantaza I would think, Yes, but what do I do?

Tilopa (a teacher at Naropa) said: don’t recall, don’t think, don’t anticipate, don’t meditate, don’t analyze, do rest naturally in the clear, luminous, bright mind. Well, that’s nice, but how? Let the cold water burn you, let it wake your bones.Because if you can do that, you’ll hear them deep inside, whispering: “Oh, what is that beautiful thing that just happened?” What is that mysterious, slightly scary, but wondrous thing that just happened?

There’s a koan in the True Dharma Eye, in which Caoshan is saying goodbye to his teacher Dongshan. Dongshan says, “Where are you going?”

Caoshan says, “I am going to the place of no changing.”

“Can you leave from the place of no changing?” Dongshan asks him.

Caoshan said, “Leaving is not change.”

But if everything is change, how can there be a place of no change? How do we get there? Is it even a real place? Can life happen there? What good is it? And if we do, somehow, succeed in getting there, how do we leave? That’s Dongshan’s question.

If there’s no change and no possibility of change, then how can you possibly enter or exit this place? “Leaving is not change,” says Caoshan. Dogen says: If you activate without leaving the monastery, you do not leave the monastery.

Bring down the walls. Don’t build them if they are not there. See they were never there, and you don’t actually need them. You don’t need them to keep you safe because that’s not real safety, and certainly it’s not freedom.

And still, there is the world, and there is the Monastery, and they are not the same. Otherwise, why have monasteries to begin with? Why spend five years or ten, twenty years or thirty, sitting steadfastly without speaking and without leaving the Monastery—an activity in which even buddhas cannot equal you? There is something in this steadfast sitting. In this uninterrupted, undivided, immersion in stillness and silence. This thoroughgoing study of body and mind.

They are also not different, the monastery and the world, or Dogen couldn’t say if you “activate without leaving the monastery,” you don’t leave the monastery. Otherwise there wouldn’t be a place of no change for Caoshan to go to. A place in which leaving is not change.

What would you tell yourself? Knowing what you know about yourself now, what would you say to yourself?

We speak so often of realization, of enlightenment, of awakening. At the beginning of the week, Roshi encouraged us to be serious about our awakening. And this too is a process. This too is change. To illuminate what is dark doesn’t happen just once. It doesn’t happen completely or infallibly. Enlightenment definitely doesn’t protect you from life, from yourself, or from your karma. It does illuminate it, so hopefully you can work with it more skillfully. But that takes time. As long as we conceive of enlightenment as an ideal state in which we’re always internally consistent, in which we don’t hurt one another or make mistakes. As long as we see it as something other than living a true human life, we will be disappointed.

And frankly, that ideal would be boring. I would rather have all of the ups and downs. I would rather ride those 10-foot waves than coast on a sea of glass. Glass is nice every once in a while, but not forever. There is no growth there, there’s no expansion. You know, one of the whispers I keep hearing is, “You can’t discover the new while hanging on to the old.” You also can’t find out what you don’t see if you keep looking in the same corners.

Here’s another poem that was offered to me and that I’ll leave you with.

Tea at the Palaz of Hoon

by Wallace Stevens

Not less because in purple

I descended the western day through what you called the loneliest air,

not less was I myself.

What was the ointment sprinkled on my [hair]?

What were the hymns that buzzed beside my ears?

What was the sea whose tide swept through me there?

Out of my mind the golden ointment rained,

And my ears made the blowing hymns they heard.

I was myself the compass of that sea:

I was the world in which I walked, and what I saw

Or heard or felt came not but from myself;

And there I found myself more truly and more strange.

Explore further

01 : At Blackwater Pond by Mary Oliver

02 : "Expressions” by Master Dogen

03 : Tea at the Palaz of Hoon by Wallace Stevens